All Over The Map: Have you seen the ‘Whidbey Island Man’?

Feb 4, 2022, 5:12 AM | Updated: Oct 25, 2022, 4:24 pm

He’s been a big friend to U.S. Navy aviators in the Northwest for more than 50 years, offering a friendly greeting to weary pilots headed for home after everything from short training missions to months-long deployments. Meet “Whidbey Island Man.”

This is an aviation story about an unusual geographic feature, most readily seen via radar, and a nickname that likely dates to military pilots of the 1950s or 1960s. The setting for this story is, not surprisingly, Naval Air Station Whidbey Island.

Richard Hart grew up in the Seattle area. He went to Mount Rainier High School and the University of Washington. He’s 74 now and lives in Island County. Hart retired after serving in the Navy and then working for many years as a commercial airline pilot.

As a young aviator who’d trained in Pensacola, he was assigned to Whidbey Island in 1971. He was already a qualified naval aviator before he arrived, but since he was a new guy at the base near Oak Harbor, Hart had to do some training flights in the area in the Grumman A-6 Intruder he already knew how to fly.

“I had an instructor bombardier/navigator in the right seat, I was flying in the left seat,” Hart told ����Xվ Newsradio earlier this week. “And he said, ‘OK, I got Whidbey Island Man.’ And I kind of went, ‘What?’ and he said, ‘Look at the radar here.’”

On the radar screen that was standard equipment in the instrument panel of an Intruder in 1971, Hart says, land masses, including islands, showed up as light, and water read as dark.

“We were about 130, 140 miles out [from the Naval Air Station], and he showed it to me, and I said, ‘Well, I’ll be darned. It really is. It looks like a man down there,’” Hart said.

What the radar showed between Whidbey Island and Camano Island was the dark silhouette of a giant man – perhaps 40 miles in length, oriented north to south, with the head at the top, with 15-mile arms and 20-mile legs. Seeing that silhouette of “Whidbey Island Man” on the warplane’s radar screen, Hart learned on that first flight, meant the aircraft was about 30 minutes from home.

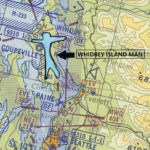

����Xվ Newsradio provided Hart with a detail from an old aeronautical chart centered over Whidbey and Camano. Hart marked it up, drawing the silhouette and filling it in with light blue, and adding a smart-looking label that matched the font and style of other labels on the chart. Hart’s enhancements show that Oak Harbor and Crescent Harbor form Whidbey Island Man’s head; Penn Cove on Whidbey Island is an arm; Holmes Harbor on Whidbey Island is a leg; and the waters of Saratoga Passage – and the west coast of Camano Island – form the other leg, the torso, and the other arm, too.

“He actually kind of looks like a Sasquatch a little bit without filling in all the internal parts, but just the outline,” Hart said.

With Whidbey Island Man signaling that the aviators would soon be returning to base, the giant silhouette served another practical function – which might remind some ����Xվ Newsradio listeners of a certain Auburn railroad engineer who tooted his steam whistle to let his wife know he was almost home. Sighting “Whidbey Island Man” inspired a similar scheme for Richard Hart and other pilots.

“If we had a good guy on the phone in the Duty Office” at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Hart said, “we’d radio into him and say, ‘Hey, can you call the wife,’ or some guys [would say] ‘Call the girlfriend – and have them come pick me up? We’re going to be there in about a half hour.’”

Hart doesn’t believe the “Whidbey Island Man” nickname or the geographic feature’s helpful arrival alert or ride-hailing functions have ever been adopted by civil or commercial pilots. It seems like this phenomenon is, or was, restricted only to Naval Air Station Whidbey Island – so it’s possible that it has only been known and spoken of by a few thousand Navy aviators since the 1950s.

After serving as one of those aviators and then retiring from the Navy, Hart was a pilot for Northwest Airlines for many years, including a decade flying 747s on the Seattle-Honolulu route and on international trips between Asia and North America. He says timing of flights – at night – and cloudy weather, as well as the specific path of the jetliner, meant only occasional glimpses of Whidbey Island Man as a commercial pilot.

“On the HNL-SEA flights, it was usually zero-dark thirty local time on the Seattle arrival, so there wasn’t much to see,” Hart wrote in an email. “Heading into SEATAC from HNL we would usually coast in over Hoquiam, so most of the time it was dark below, with only the lights of the cities and highways as visual references.”

Whidbey Island Man can likely be seen without radar, Hart says, but you’d have to be at about 10,000 feet, maybe 30-50 miles south of Whidbey Island, and have clear weather.

“The Whidbey Island Man ‘pops’ on radar, as there’s not too much other clutter to confuse one’s perceptions of what is/is not the Whidbey Island Man,” Hart wrote.

“When flying from Tokyo, Hong Kong, Seoul, Osaka, etc. to points farther east (Chicago, Minneapolis/St. Paul, NYC, Detroit, etc.),” Hart continued, “we’d usually pass Whidbey Island in the early morning hours and if it wasn’t ‘winter dark days’ … and it was clear … we’d be treated to the entire Puget Sound basin and a vista that spanned from Garibaldi in Canada to Rainier, St. Helens, Adams, and occasionally Hood to the south. Quite a show.”

One other thing Hart might see looking down on Whidbey Island from that left seat of the Northwest Airlines 747? His own house, of course.

After all, like the arcane silhouette that’s been beckoning aviators for decades, Richard Hart is something of a Whidbey Island Man himself.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News, read more from him here, and subscribe to The Resident Historian Podcast here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.